Knowledge Base

Gender survey in the Talgar District of Alma-Ata Province

Study areas

For this gender survey was selected the Talgar District of Alma-Ata Province.

The Talgar District of Alma-Ata Province was established in 1969 and is located in the east from Alma-Ata City in foothills of the Zay Alatau Ridge. The district borders with Enbekshi-Kazakh District. Climate is extremely continental with hot summer and cold winter. Topsoil is mainly represented deep-brown soils, which is replaced by grey soils in the southern portion of the district. Glacial-fed mountainous rivers are the following: Talgar, Besagash, Terenkara, Kutentay, Jalgami, and others. Water for irrigation of crops is supplied from 12 seasonal-regulated reservoirs, the BAC and the Talgar Main Canal.

The total area of the district is 464,551 hectares. The administrative center is Talgar Town, which was established in 1858. The town is connected with other cities and settlements by motor, railway, and air transport via Alma-Ata. The Alma-Ata State Reserve is located on the Talgar District’s territory. There is the wide network of health and holiday centers in this region. The population is 163,000 people.

Industrial enterprises produce construction materials (crushed stone, sand, brick etc.) and manufactured goods such as printed output, package, detergents, ready-made garments, frameworks for nomad's tents etc., as well as mini-tractors and drugs are produced here. There are enterprises of food industry in the district.

The agricultural sector is presented by 2642 agricultural enterprises and complexes including 26,042 peasant farms, 3 joint-stock companies, and 21 co-operatives. There are 46,750 hectares of arable land in total, and the sown area is 44,196 hectares. There are 39 schools and 4 colleges in the district. 34 medical centers provide medical services for the population. There are sport halls and stadiums, three cultural centers, and two clubs.

Households and their owners

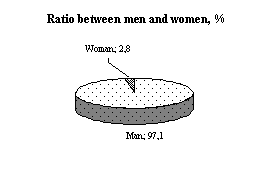

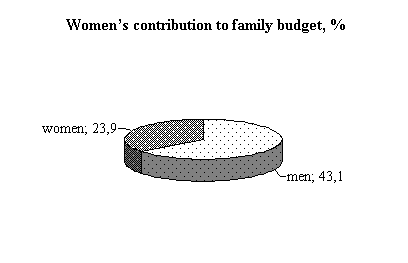

Seventy households with 653 residents were surveyed. Figure 1 shows the ratio of men and women who head households.

Fig. 1

General characteristics of households and their sizes

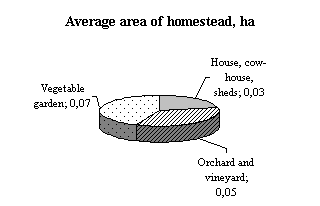

The rural type of households was selected to carry out this gender survey. Each family actually has its garden plot where they cultivate food crops and raise livestock. Fifty five percent of families have fields where they raise wheat and other various crops. Fields’ sizes are different and range from 0.5 to 30 hectares. Figure 2 presents data (average data per one family in the district under consideration) on areas occupied by houses, garden plots, and fields. Figure 2 shows that, on average, a size of a yard including a house with adjoining sheds, cow-houses and other premises is 0.03 ha. This area is insufficient for raising a large quantity of cattle. An average area under a garden plot belonging to one family amounts to 0.07 ha. They cultivate vegetables on their garden plot mainly for their own consumption. In the most cases, women and men are equally using their garden plots; moreover, traditionally men are engaged in land leveling, tillage, and irrigation, and women in planting and weeding. Usually, all members of the family participate in harvesting. Thus, all members of the family cultivate their garden plot, and the yield is mainly used for their own consumption. Women are generally engaged in fattening of cattle if this is not a specialized livestock farm.

Fig. 2

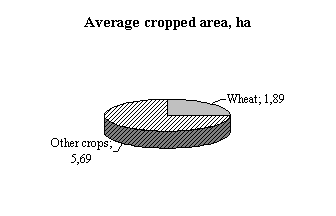

In some cases, the family has cropland, which is a long-term tenement with the right of succession. Sometimes a few families establish co-operatives, and in this case, they are actual farmers because they become the legal entity, have a bank account and can take credits. Peasants raise wheat and other crops (sugar beet, potato, vegetables and melons, as well as fodder crops). Figure 3 shows that, on average, one family has about 7 hectares of cropland. At the same time, about 20 percent of all cropland are sown by wheat.

Fig. 3

Vegetables and fruits grown on garden plots are quite diverse (Table 1) Most families (70%) raise cows in their households. 68.57 percent of families are busy with chicken farming, and 37.14 percent of families raise sheep (Table 2).

Composition of a rural family

As a rule, the Kazakh rural family is numerous. An average size of the family amounts to six people (8.5 percent of families consist of 3 to 4 persons and 34 percent of families consist of 7 to 10 persons). Usually, the family consists of two spouses and children, whose number ranges from two to five people. Sometimes, aged parents live together with them. Table 3 shows an average composition indicator of one average rural family (Column 2) and the percentage of its members (Column 3), if the total number of members living in a household is taken as 100 percent.

Birth rate

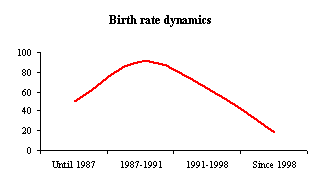

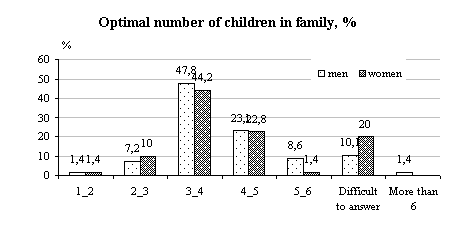

The analysis of rural families’ composition (Fig. 4) shows that the birth rate curve steeply descends after 1991. A birth rate has dropped more than four times, in comparing with the period at the beginning of the 1990s. It is necessary to note that prior to the beginning of the 1990s the birth rate was raising but later the situation has drastically changed. Kazakhstan is not exclusion from the trend prevalent over the entire post-Soviet territory related to decline in a birth rate last years. A way of life and traditions formed in the republic during many years predetermine the presence of many children in families. For a long time, Kazakhs had a nomad's life moving over wide steeps of Kazakhstan. Under living in remote places from settlements without some medical care, their children born in such conditions were deprived of timely vaccination and other medical aid, and some of them did not reach the adult age. Therefore, in the past, families had to have many children since they kept in mind that not all children would survive. Of course, this is not the only reason for the possession of many children in oriental families. There are many causes, but now we do not review all of them. In spite of many changes in life conditions of Kazakh rural inhabitants, the deep-rooted opinion regarding an amount of children exists until now. Most respondents consider that an ordinary family should have, on average, 3 to 4 children (the opinion of 47.8 percent of men and 44.2 percent of women) or 4 to 5 children (the opinion presented by 23.1 percent of men and 22.9 percent of women) (see Figure 5).

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

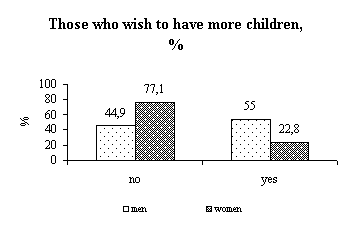

This diagram shows that opinions of men and women regarding an amount of children are approximately identically distributed. However, due to a different age pattern (an average age of men is more than 40 years and of women less than 35 years) their opinions are disagreed. As a rule, these are organized families with many children. Therefore, owing to their age, most men (77.1%) gave the negative answer to a question: «Do you want to have any more children?» (Figure 6). At the same time, 55 percent of women answered that they are ready to become a mother once more.

Fig. 6

Marriage age (nobility)

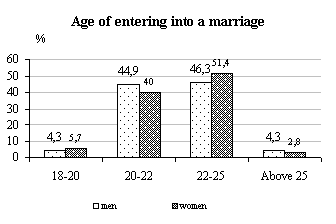

Figure 7 shows that the picture of marriage of rural residents is rather non-traditional. The settled way of life, the higher level of education, and many other factors have exerted influence upon the behavior and the way of life of modern rural inhabitants. Early marriages remained in the past. Most women get married at the age of 20 to 25 (40% and 51.4% respectively). At the same time, men create their families mainly at the age of 20 to 30 (40% and 46.3% correspondingly). Actually, men and women create their families at the age when they, physically and morally, are ready to create the family and to have children. By the time of marriage, they acquire a profession and are able to endow their families. According to respondents, there are mainly love-matches; however, opinions of parents and older members of the family are taken into consideration. Nevertheless, young people themselves make final decision.

Fig. 7

Economic aspects

Forming the rural family’s budget

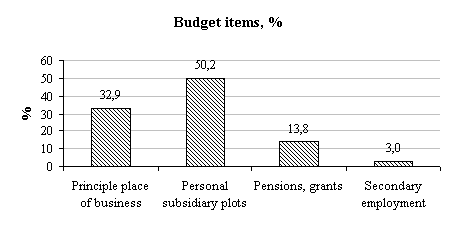

According to collected data, main sources of households’ income (Figure 8) are the following:

- personal garden plots;

- labor at a permanent place of employment or temporary work for a wage, by one or all capable members of the family;

- state funds allocated to specific social groups of the population in the form of pensions, benefits, grants etc.; and

- secondary employment;

Other sources of income do not play an essential role in the family budget. Main sources of income of rural residents in surveyed villages in Kazakhstan are the following: income generated on personal garden plots (50.2%) and wage works (32.9%). In this case, income generated on personal garden plots implies money resulting from sale of produce grown on fields rented for a long-term period. 49.28 percent of men and 37.14 percent of women consider that these earnings are the basis of their budget. It is necessary to note that practically all men are farmers, and women are mainly workers hired by farmers, or they work on the farms of their husbands. Income received from permanent jobs is wages from state institutions and organizations. 46.38 percent of men and 28.57 percent of women have such earnings, which are relatively stable. Women work in schools, kindergartens, hospitals, and companies in the food and pharmaceutical industry, etc. Men work in factories that manufacture construction materials, as well as drivers etc. However, most of the so-called farmers are not really farmers because they do not the status of a legal entity and a bank account for commercial activity. Only five percent of respondents have established co-operatives and have the status of farmer as stated by the law. The rest of the population, approximately 4 percent of men and 34 percent of women combine a part-time paid job with agricultural activity.

Fig. 8

Input of pensioners and members of the family those receive state benefits into the family budget amounts to 13.8 percent. It should be noted that this income is exclusively based on payments to retired people, disabled people, and children up to the age of 18 in the form of state pensions and benefits. Income related to secondary employment amounts to 3 percent. However, it should be mentioned that only 5 percent of men and 0.3 percent of women have secondary employment.

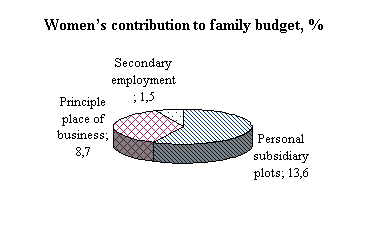

Input of women into the family budget (Fig. 9) is less than that of men by 1.8 times, in spite of the fact that women are more engaged in housekeeping, and this workload is very heavy, but is difficult to measure in money terms. The greatest share of women’s income (13.6%) is generated from work in the fields (Figure 10); their labor in full-time jobs generates only 8.7 percent of income.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Income per capita can be used as an indicator of the standard of living. It amounts to US$ 54.8 per month in Kazakhstan. Only 3 percent of respondents gave a positive answer to the question: «Does current family income satisfy you?» It must be said that income per capita in Kazakhstan is variable. It depends on annual yields, market prices etc. 2005, when this survey was carried out, was considered by rural inhabitants as an unsuccessful one with respect to agricultural output and hence earnings.

Expenses of rural families

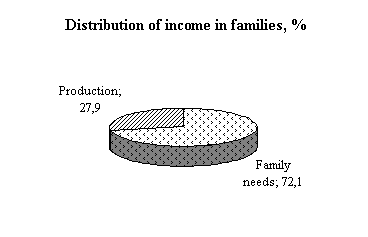

Earned income in rural families (Fig. 11), first of all, is distributed between the needs of the family itself and the production costs. The production costs include expenses for developing garden plots, purchase of seeds, household implements, and young cattle for fattening, as well as expenses for soil treatment and crop growing. Figure 2.4.12 shows that the production costs amount to 27.9 percent of income.

Fig. 11

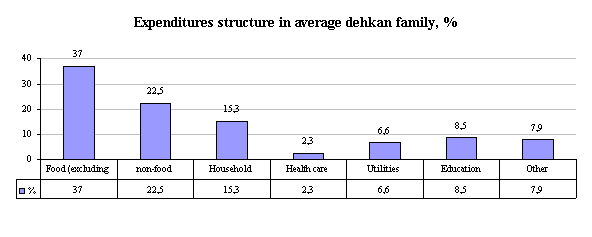

In their turn, funds allocated for the needs of the family are used for financing a number of items necessary for supporting the family’s life (Figure 12) that consist of the following:

- foodstuff;

- non-food items;

- household needs;

- medicines and medical services;

- public utilities services;

- education; and

- other expenses.

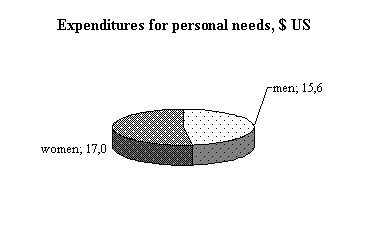

Fig. 12

Expenses for foodstuff are a very important indication of family’s welfare. If these expenses exceed 20 percent of income then the income cannot be considered as sufficient. In our case, expenses for foodstuff, on average, make up 37 percent of income. However, it is necessary to note that the difference in expenses for food within the republic is considerable (from 15% to 60%) The proportion of families whose expenditures for food do not exceed 15 to 20 percent is negligible, only 2.6 percent of all surveyed families. Expenses for medicines and medical services (2.3%) are also extremely small. Taking into consideration our attention to gender aspects, expenses of men and women for their own personal needs (for example, expenses for hygienic materials etc.) are of interest. Men and women cannot satisfy their personal needs in full; however, in Kazakhstan these figures are relatively high and amount to US$ 15.6 for men and US$ 17 for women, on average (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13

Foodstuff consumption

Nutrition is the process of entry and assimilation by the human body of nutrients necessary for replenishing energy consumption, building up and recovering tissues. Nutrition, as an important component of metabolism, provides links between the human body and the environment. Correct nutrition affects a human being’s health, his ability to work, and life span. There is a concept of rational nutrition, and its disturbance can result in different diseases.

The amount of foodstuff consumed is quite different not only between families but also between regions. Regional differences are caused by the location of residence and national, religious, and other traditions. A specific diet (quantity and quality of different foodstuff) of each family depends on the financial status of the family, tastes and the level of health of its members, as well as the age structure. However, there are so-called medical rates of food consumption, and their infringement results in abnormalities in development and vital functions of a human being. One should not associate these medical rates with a basket of goods, which directly depends on the economic status of the region as a whole. These medical rates can be considered as the standard for the balanced nutrition. A specific amount and combination of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, minerals, and vitamins provide calories to a human being’s organism, ensuring his mental and physical abilities.

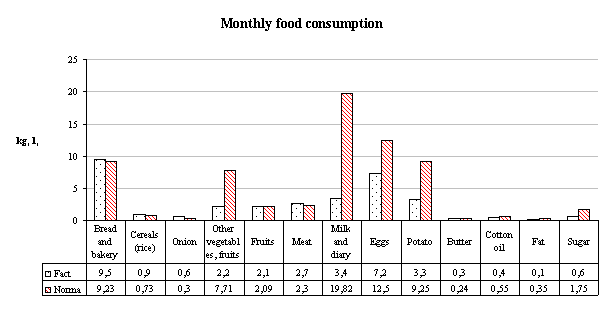

The following situation was revealed in the process of analyzing foodstuff consumption in an average rural family in Kazakhstan (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14

Nutrition in an average rural family in the surveyed districts of Kazakhstan is rather peculiar. Kazakhs are always considered as cattle-breeders, and therefore meat consumption slightly exceeds the nutrition norms in their diet (actual consumption makes up 2.7 kg/month against 2.3 kg/month according to the norms), but consumption of other food containing proteins, such as dairy products, eggs etc. is considerably less than rates. Carbohydrates are mainly consumed in the form of bread and bakery items, and consumption of sugar and vegetables is less than biological rates. Consumption of fruits is at an acceptable level. Such nutrition cannot be considered as a completely balanced diet.

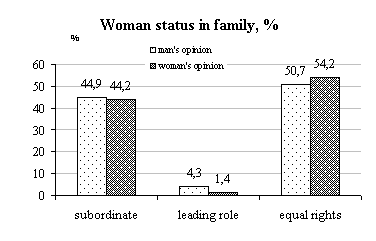

Gender status in a family

As has been shown in this survey, opinions on woman’s status are practically divided in half. Approximately in half of Kazakh men and women define the role of women as “subordinated persons”, and half consider the position of a woman as equal to a man (Figure 15). 50.7 percent of men and 54.2 percent of women admitted equality of women.

Fig. 15

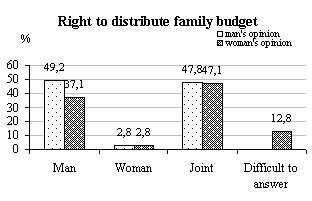

An indicator of actual equality in rights of women within families can be the right to manage the family budget according to her discretion i.e. to have access to financial resources, and to make decisions. A woman can possess this right if she has economic independence from her husband or other members of her family. As mentioned above, the income of women is two times less than the income of men. However, only 2.8 percent of respondents (men and women) consider that women have the right to manage the family budget; 49.2 percent of men and 37.1 percent of women consider that only men can do it. 47.8 percent of men and 47.1 of women think that all decisions regarding expenses should be jointly made (Figure 16).

Fig. 16

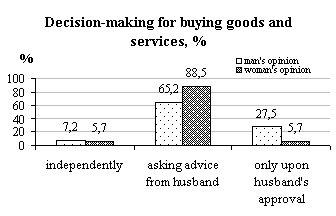

The right to participate in decision-making regarding a purchase is the important indicator of the status of women in the family. In this case, purchasing of goods and services (regardless their costs) for family’s needs is kept in mind. The overwhelming majority of men (65.2%) and women (88.5%) answered that women ask advice of their husbands before making any purchase (Figure 17). 27 percent of men consider that women can make a purchase only after receiving the permission of their husbands. In these cases, self-dependence of women is not permissible.

Fig. 17

Labor and employment

Employment of rural men and women

Findings of the gender survey show that in a rural family, both spouses are both actual and necessary “bread-winners.” It allows speaking about the almost equal responsibilities of men and women for welfare of their families. The analysis performed enables us to draw a conclusion that women are working in the public sector, in farms, and on personal garden plots, and, at the same time, they are busy in all housekeeping work and duties such as cooking, laundering, cleaning, and care for children and aged people. However, the time deficit limits the women’s potential to participate in public production in full measure. A woman, who is engaged in managing her personal garden plot under conditions of lack of specific machinery and sufficient funding and in housekeeping, which cannot be evaluated in money terms, apparently has income in cash equivalent less than a man. Growing and sale of agricultural product on garden plots generate extremely low income. Thus, one can say that rural women are mostly engaged in producing non-market output. As a rule, if women are working in the public sector, they work at low-paying jobs.

Time budget

We asked respondents to describe their daily routine in order to have more detailed information on the division of labor between men and women in the rural area regarding both income-generating activity and housekeeping. Figure 1 shows data averaged through the week (also see Annex).

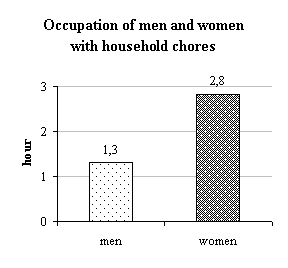

The key matter of the gender problem is rural employment (both men and women). As has been mentioned, the main source of rural families’ income in surveyed districts of Kazakhstan (50.2%) is farming on the rented land plots. As was identified, income of women is about half the income of men. However, if we take into consideration that a woman carries out actually all housekeeping works and duties including cooking, laundering, cleaning, and bringing up children, it become obvious that she is engaged considerably more than a man. In comparing with a man, a woman spends her time for housekeeping more than 2 times (Fig. 18). The diagram shows how much time per a week men and women are engaged in both socially useful works and housekeeping (Annex). In Table 4, we tried to show the time proportion in the workload on men and women in percent. “100 %” was taken as the value, designating the workload on women. Data of this table make it clear that men spend more time for a wage work (1.4 times) and working on their garden plots (only 1.1 times). Men are busy with visiting a market, watching TV, and fulfilling devotions 1.1 times more. Women spend for cooking, laundering, washing, and nursing, on average, more than 9 hours a week in contrast to men, who practically do not do these activities.

Fig. 18

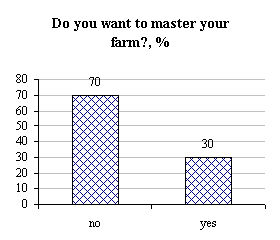

Based on above, it is possible to draw a conclusion that in the overwhelming majority of families, a woman carries out housekeeping duties. She makes her input in the form of manual labor for maintaining some comfort and cleanness in her house and cooking in spite of her work in the public sector and on her own garden plot. It is the fact that women practically do not have time for valuable leisure and entertainment. Therefore, Kazakh women gave a negative answer to a question concerning their wish to manage their households (70 percent of women gave a negative answer against 30 percent of women who gave a positive answer) (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19

Education and cultural aspects

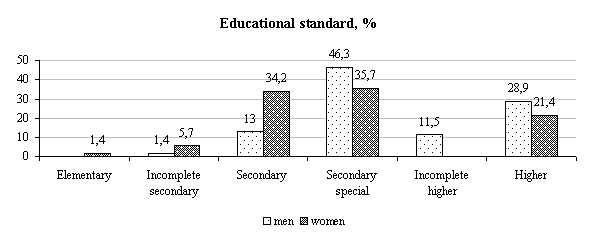

This survey has shown that the level of education of rural inhabitants is relatively high (Fig. 20). Almost a half of all men living in the region under consideration (46.3%) have special secondary education. 35.7 percent of women also have special secondary education. 28.9 percent of men and 21.4 percent of women graduated from different universities. However, this is not always agricultural education. Therefore, their education is enough for managing their personal garden plots but in order to establish and to manage a real private farm, rural residents should gain additional knowledge in the agricultural practice for successful farming management.

Fig. 20

Nevertheless, their potential abilities are rather high; however, the existing conditions do not allow putting their professional skill in practice in full measure and some of them are obliged to learn again in order to gain such a profession, which is called for at present. However, taking into consideration that the economy of this country is on the rise as a whole, and there are positive shifts in the agricultural sector too including development of market relations, there is the hope that in the future, the number of farms will increase and farmer’s associations will be established. All activities will be built up on the scientific basis. As a result, well-educated people will be called for, and everyone will be able to find adequate application of his knowledge. 34.2 percent of women have secondary education i.e. they left a secondary school. As a rule, men and women leave a primary school in their villages. Persons wishing to continue their training should go to cities or regional administrative centers.

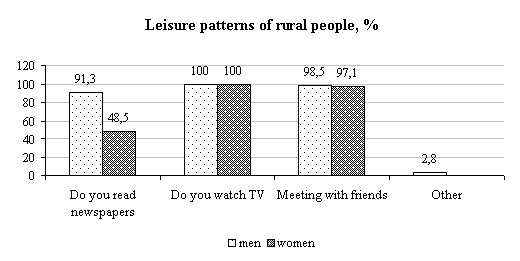

Leisure and entertainment of rural inhabitants is rather monotonous (Figure 21). Due to the lack of functioning cultural institutions (cultural centers, clubs, cinema theatres etc.) most respondents have quite limited possibilities for valuable leisure. Almost one hundred percent of inhabitants prefer watching TV and meetings with friends as entertainment. Young people prefer mainly to visit clubhouses; at the same time, older people prefer to read newspapers.

Fig. 21

Medical care

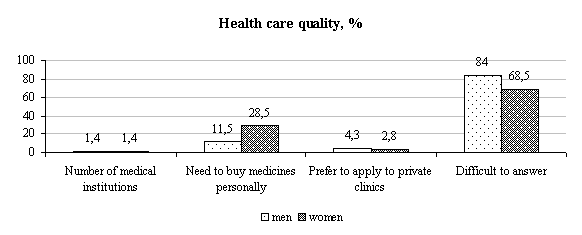

Rural residents do not generally have the specialized medical aid posts in their residential area and, therefore, they have to go to a polyclinic or a hospital in the regional administrative center to receive qualified medical services. Data of the gender survey shows that only 2.8 percent of women and 4.3 percent of men prefer to visit private clinics for medical aid (Fig. 22). 68.5 percent of women and 84 percent of men found difficulty in answering given questions. Such results confirm that medical care in Kazakhstan is unsatisfactory.

Fig. 22

Priority goals and personal features necessary for achieving success

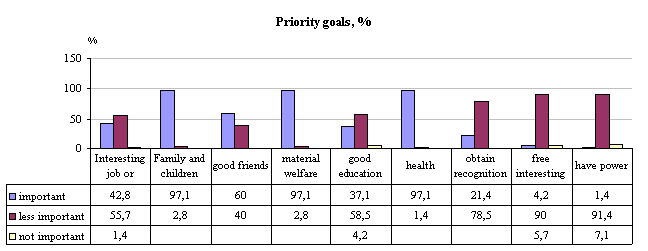

Female respondents were asked to answer the following question: what goals do they have in their life? What does each woman aspire to in order to make sense of her life, to gain satisfaction, and to feel needed by her family and other people? Data of the gender survey shows that family’s happiness and welfare are the leading goal for rural women, and active participation in the social life is the secondary aspect of their life (Fig. 23).

Fig. 23

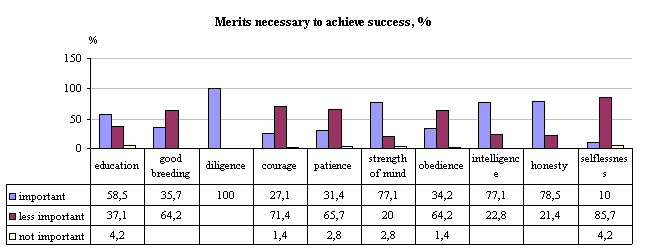

Women specified intellect, diligence, to be well-bred, honesty, adherence to principle, and education as chief personal features necessary for achieving success. They consider such features as strength of character, perseverance, selflessness i.e. those features that promote to be an active member of society as secondary features (Fig 24).

Fig. 24

Water use

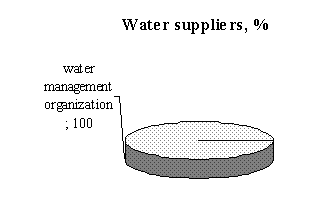

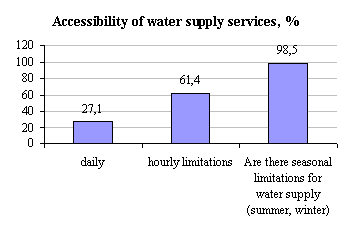

The water management organization renders one hundred percent of services on domestic-potable water supply to the population, institutions, and organizations of districts where irrigation water is a main source of water supply (Fig. 25). Not all rural residents in study regions faced water use problems equally. The level of water supply is directly related to the seasonality, for example, there are irregularities of water supply in the spring-summer period. As a whole, it is possible to assert that water supply is not always equal and regular (Fig 26).

Fig. 25

Fig. 26

The overwhelming majority of respondents (98.5%) consider that there are seasonal limitations in water supply, and 61.4 percent of respondents consider that there are also hourly limitations in water supply; and 27.1 percent of respondents assert that there are no problems with water supply.

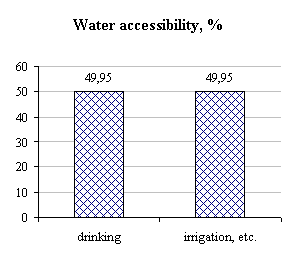

Only a few households have full access to the water-pipe systems. Regarding irrigation water, it is possible to assert that some villages do not face water deficit for irrigation and domestic uses. Although there are some seasonal and hourly limitations in water supply, however, a half of all respondents consider that potable water (49.95%) and irrigation water (49.95%) are quite accessible even in the summer period (Figure 27).

Fig. 27

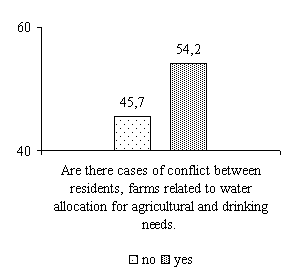

According to 54.2 percent of respondents, water conflicts among inhabitants take place in the summer period, and they are settled not always peacefully. To settle disputes sometimes interference of the local government or aksakals (elders) living in that locality is necessary. The priorities are specified on the basis of mutual agreements, first of all, taking into consideration the needs and importance of water supply for specific uses. 45.7 percent of respondents consider that there are not causes for water conflicts (Fig. 28). Most respondents (80 %) consider that it is necessary to put water-saving technologies into practice for household water supply and irrigation. Only one third of respondents could answer what measures should be employed for proposed water saving.

Fig. 28

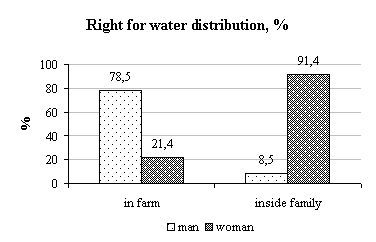

By the example of water allocation, it is possible to show that women have quite limited access to the decision-making process (Fig. 29). They can distribute water in their own household (91.4%) but not at the farm level. Since they completely manage housekeeping, water use in households is the priority of women. It may be mentioned that women have possibilities to distribute water at the farm level only in 21.4 percent of cases. Water charging was introduced in this country; at the same time, the fee is too low, and, therefore, rural inhabitants do not have problems to pay for water services.

Fig. 29

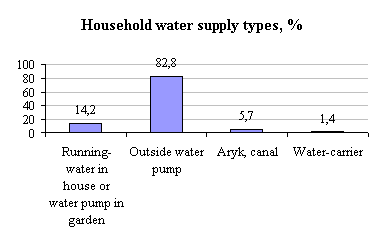

Household water use

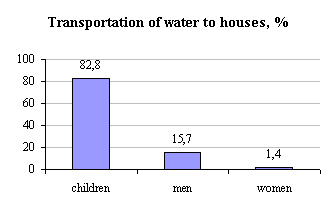

According to data of the gender survey, only 14.2 percent of rural households have a water-tap in their yards (Figure 30). The overwhelming majority of respondents who do not have a water post in their yards take potable water from a water post in the neighborhood (82.8%), 5.7 percent of respondents take water from the irrigation network. Figure 31 shows that teenagers are mainly busy with domestic water supply (82.8%). Men (15.7%) also participate in domestic water supply. They spend for water supply from 15 minutes to one hour every day.

Fig. 30

Fig. 31

Inhabitants, who do not have tap water in yards, use approximately the same option for water storing. Everyday, water is filled and stored in big metal flasks or in other adequate tanks.

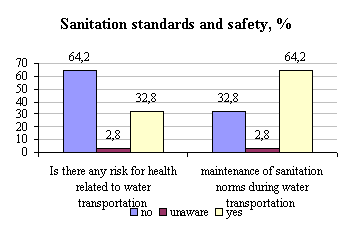

A very important aspect is sanitary conditions for water supply, and water quality and safety, which residents do not adequately realize. Water that they use and the way of its delivery to households are not always secure for their health. The places of water withdrawal are not always equipped with proper and safe facilities. Water is delivered using bicycles and specially equipped handcarts. Most rural residents consider that it is enough to boil water, and it will meet all water safety standards. Figure 32 shows that answering the question concerning observance of sanitary standards, 64.2 percent of respondents consider that water completely meets the sanitary standards, and there is not any risk to use this water. In contrast, 32.8 percent of respondents consider that water does not meet the sanitary standards. 64.2 percent of respondents consider that the way of water delivery does not cause any risk for their health.

Fig. 32

Land use

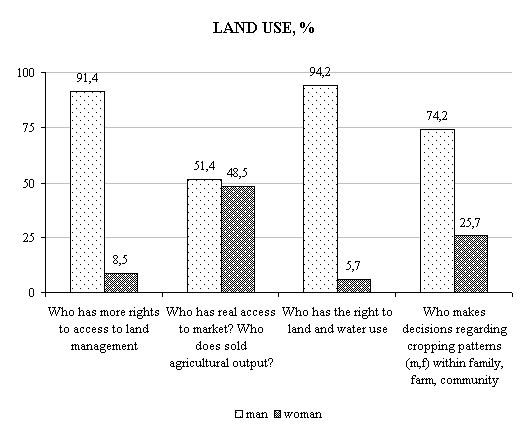

Because rural residents are land plots’ owners in a practical manner, they have quite certain ideas about priority rights regarding land ownership (Fig. 33).

Fig. 33

From 51 to 94.2 percent of respondents consider that only a man:

- allocates land plots for vegetable gardens;

- has access to agricultural machinery;

- has access to a market;

- has the priority in receiving credits;

- posses land and water use rights;

- makes decisions in regard with a crop pattern in a farm; and

- has real access to a ready sale.

In respondents’ opinion, about 48.5 percent of women may have access to the agricultural market. It seems they keep in mind the small-scale wholesaling of vegetables and fruits from their household plots. 25.7 percent of respondents consider that women may make decisions concerning a crop pattern both in their households and in co-operative farms.